I was wrong. I’m sure there are still holes in my theology. The aim of this admission is to describe my journey towards understanding my privilege as a white woman and the ways that racism permeates systems in the USA. My narrative traces my journey in the hopes that my vulnerability will allow others to begin or continue their own journeys to understanding how power and privilege have been woven into the fabric of our nation. For readers who identify themselves as Christians, I hope that the explanation of my old and new theologies will push you to reread the ancient text with new eyes, ready to reexamine your own beliefs with the Holy Spirit’s guidance.

Growing up in a white evangelical world

Curled up in a corner, as a child, I turned page after page, absorbing stories of the resistance during World War II, abolitionists on the Underground Railroad, and suffragettes at the turn of the century. My inarticulate heartcry for as long as I can remember has been to help others by defying injustice. Problematically, though, in the 1990s, it seemed as though the only real problems were overseas. There didn’t seem to be any problems in my world, one where my middle class family lived on one income and my college educated parents devoted themselves to my education.

Our family was surrounded by other white people, with a few notable exceptions. Since my family was really good friends with a Southeast Indian family, a biracial family, a Chinese family, and my cousins hosted exchange students frequently, I thought I had a diverse community. I didn’t. My friends’ black dad told us stories of getting pulled over by the police for being black in the wrong neighborhood, but aside from his stories, I thought racism had ended during the Jim Crow era.

First exposure to “otherness” and the minority experience

In college, I worked at an almost-all black summer camp. Curiously, conversations on race happened all-the-time. As in every day. Multiple times a day. As one of four white people in a camp of two hundred kids and staff, I was acutely aware of being white. Other than a few weeks stint in India, this was my first time when I wasn’t part of the majority. Patiently, my camp friends explained the nearly constant awareness of “otherness” they experienced. Sitting in a Panera on our day off, two of my mixed friends asked me: “Did you notice that we are the only brown people here?” “No,” I remarked, surprised, as I looked around and observed they were right. “We did,” they replied, “the moment we walked in here with you.”

After college, I taught high school English at a charter school whose students were primarily white. Race didn’t seem to be an issue there, or I didn’t think it was, until one day I was talking to one of my brother’s best friends. She told me about her dreadful experience as one of the only black students at the school a few years prior. Accused of supporting the Obama administration, she was bullied, beaten in the locker room, her family was threatened, and racial epithets were spray painted outside her home. Crying, I listened to her experience at the school, heartbroken and confused. It just didn’t make sense. How could her experience there have been so different from my own?

My incomplete understanding of the gospel: seeing the cross through an individualistic lens

While teaching, I started a master’s degree at Denver Seminary. My original goal was to go overseas to fight sex-trafficking. During the four years I spent at seminary, my understanding of the Gospel was fundamentally changed, which has allowed me to have an intellectual framework wherein I have space for categories like systemic racism.

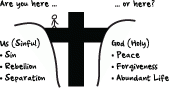

You see, up until I began my master’s program, my framework only had space to see the world in terms of individuals. My own upbringing using this framework meant that I didn’t see race as a problem because I wasn’t a racist and I wasn’t friends with racist people. As a Christian, my worldview was rooted in my understanding of the gospel. Herein lies the problem: the version of the gospel I grew up with was too narrow and was therefore incomplete. It went something like this: People are sinful and they need a savior to save them from God’s wrath. If you believe in Jesus, accept his free gift of salvation, and have a relationship with him, then you’ll go to heaven and live eternally with him there. The subtext in my especially conservative community added: “Since you’re a Christian, you should make sure that other people see you behave like one; no premarital sex, no drunkenness, dress modestly, and be nice to other people.” [1]

Here’s an illustration of what this version of gospel looks like:[2]

Ultimately, this gospel comes down to the individual and his or her relationship with God. First, I recognize that I’m a sinner and that I need Jesus, and then from there, being a Christian is about growing in my personal relationship with Him.

Using this framework for salvation, one understands sin in individual terms (lying, adultery, murder, etc.). In an individual framework, racism amounts to individuals hating other individuals with the wrong skin color. Racists are folks who use the n-word, call black men “boy,” and don’t want their kids to marry people from a different race. My understanding of economics, history, politics, etc. fit into a view of the world where individuals are able to make choices, and how they respond to those choices influences or even determines their outcomes. If black people made choices to have kids out of wedlock, drop-out of school, or do drugs, then those individuals’ choices were responsible for their poverty, imprisonment, etc. People who worked hard, like Arther Ashe, one of my childhood heroes, made it. Simple, right? Hard work equals success. Anyone can achieve the American Dream if he or she works hard enough. This idea is called meritocracy. Personal responsibility is rooted in the white American psyche as the key to one’s success or failure.[3]

A more robust understanding of the gospel: How Jesus redeems the world and us

Up until a few years ago, nothing in my education had contradicted my worldview defined by individualism and meritocracy, and as an Evangelical Christian, this worldview fit neatly with the way I read the Bible and thought about my faith. Seminary pulled the rug out from under me by forcing me to examine how I read the Bible and to question if the way I currently understood the gospel aligned with what the Bible actually says. Ultimately, study of scripture revealed that I had a narrow and incomplete understanding of sin and the gospel. This individual gospel is what had allowed me to define racism only in individual terms and didn’t explain issues like genocide or sexism very well.[4]

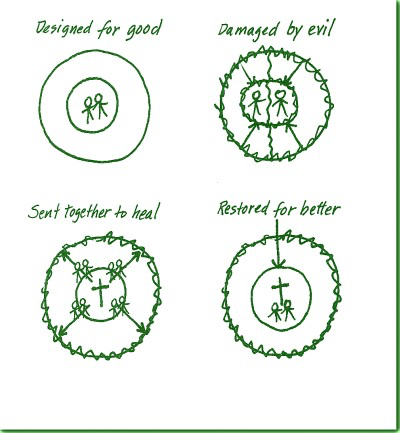

A more robust understanding of the gospel made space in my intellectual framework for categories like systemic sin. Genesis teaches that in the garden of Eden, humans were in perfect harmony with God, each other, themselves, and creation until the fateful day they sinned. When sin entered the world, it damaged those four relationships that had been intact and whole. Sin damaged these four relationships by separating us from God, creation, each other, and ourselves. The individual gospel I grew up with emphasised my separation from God and my individual sin. But it didn’t really explain why Ebola existed, or why children were soldiers, or why people suffered from mental illness, or children were raped, or genocide happened. Understanding that sin now influences all aspects of creation accounts for all that we intuitively know is wrong with the world.

If sin is this great, then salvation must be greater. Jesus’s atonement has to be coextensive with the fall. The Bible teaches that it is; Jesus’ death and resurrection atoned for the sins of the world and triumphed over Satan. Everything that had been damaged by sin in the fall, Jesus paid for in his triumphal death and resurrection. Scripture promises that Jesus is building his Kingdom and that in the new heavens and new earth all will be set right. The wholeness, harmony, and peace that characterized Eden pre-fall will once again be restored in an even more glorious way. Men and women in the church are sent out into the world to love and serve the world as ambassadors of Jesus and his glorious Kingdom. Here’s an illustration of this version of the gospel: [5]

Because the white Evangelical church teaches a version of the gospel where sin is only about the individual, we struggle to explain how the gospel is good news to the poor, the broken, and marginalized. Why is the gospel good news to survivors of genocide? Why is it good news for those who’ve been raped? Why is it good news for women? Because Jesus’ triumph defeats the Evil One and his works. Jesus redeems and restores; he makes all things new. He redeems me from my sins, you from your sins, and our world from the effects of sin.[6]

The gospel & racism

The principalities and powers of this world are opposed to Christ and his Kingdom.[7] One of the ways that the US, since its inception, has seen the effects of sin on a creation level and among ourselves is in racial oppression and disparity in how non-white people are treated. From broken agreements and the forced dislocation of native Americans, to the slave trade and oppression of African Americans, to the exclusion each new wave of immigrants have faced (Chinese, Irish, Latinx, and more), to the eugenics movement, racism has been woven into the fabric of our nation.[8]

Understanding historical racism’s systemic impacts today

The historical national sin of racism has impacted our country in such a way that the narrative of individual choices is inadequate in explaining the discrepancies in outcomes between white and black people. Claims of systemic racism point to this and explain that sin has given the black community an unequal playing field. When we look at rates of incarceration, kids in special education, and wealth disparity, we see that unless black people are more criminal, stupid, or lazy, if we discount the possibility of a systemic issue, there’s no good explanation for why they’re more likely to be in jail, on individualized education plans, or poor. Since we decry the claims that whites are superior to blacks, and as Christians believe that all are created in the image of God, then what is to explain the stark differences?[9]

Imagine a race to put together two 1000-piece puzzles. Team A for the first three hours of the puzzle is blind-folded and all members have one hand tied behind their backs. They complain this is unfair. Finally, team B agrees and Team A’s blindfolds are removed and their hands are freed. Four hours into the competition, there’s a pause and the puzzle progress is assessed. Which team has more of their puzzle constructed? What if the judges come in and don’t know about the rule change 3 hours in? Isn’t the automatic assumption that Team A isn’t as good as team B because they don’t have as much of their puzzle complete?[10]

The historical narrative I learned said that Abraham Lincoln and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. solved racism. It omitted facts about redlining, and how the GI bill gave federally-backed mortgages and college education overwhelmingly to white veterans, enabling them and their families to build wealth. Both my grandfathers benefited from the GI bill, and my parents are both college educated. [11] Growing up, the question I was asked was where, not if I would go to college. A lot of policies have disproportionately hurt black and brown communities while helping white ones.

A few years ago, when the Black Lives Matter cry had just gained national attention, I shared a friend’s blog post about how her bi-racial family had been pulled over by the police. White friends who read my post felt like I was calling all cops racists and unleashed their umbridge on me. Without an understanding of how systems can be corrupted by systemic sin, it is difficult to read a story even mildly critical of police and not feel personally attacked, especially in a career where your life is on the line every day. Americans pride themselves on holding ideals of fairness, equality, and justice. No other nation on earth has the freedom that we do, we teach our children. And yet, unless we are willing to take a hard look at our history and the ways that our ancestors (as sinful people) created broken systems (which still bear the effects of sin), we won’t be able to listen to each other or build a more perfect union.

Implicit bias in white churches & the larger community

My first job out of Seminary was working at a community center run by a white, suburban megachurch. My boss was originally from Argentina, and while he could pass for white, his accent gave away his Latinx roots. I started noticing things like other church staff mispronouncing his name or not making the effort to learn how to say it correctly. I realized that, in meetings with community partners, they would look at me when they were talking, even though my boss was the decision maker. A lot of these kinds of slights are unconscious; those folks who are doing this often have no idea they are devaluing the person of color with whom they’re interacting.

Around the same time, I started dating the man who is now my husband. He’s Tamil, from Sri Lanka, with beautiful dark brown skin. As a mixed race couple, I realized we got more looks than I’d gotten when on dates with white men. When we would go to Walmart and they had a receipt checker, that person would never ask to see our receipt if I was pushing the cart, but if Edgar was pushing it, we would almost always get stopped. It didn’t matter if the receipt checker was Black, white, Latinx, or Asian. Because Edgar’s darker than me, he doesn’t get the same presumption of innocence that I do.

Raising brown kids & learning about my own privilege

As I considered writing a post on race, I hesitated for a lot of reasons. One is that I don’t have all the answers, and I’m still learning. But if I’m going to be honest, I realize that I still have a lot of implicit bias and privilege at work in me. I get frustrated sometimes that Edgar is less willing to go into stores or handle administrative tasks; “how hard is it really to register the car / make a return / deposit money at the bank?” I ask myself. But the reality is that the system works for me because I’m white: when I go to stores to make a return, I can, no questions asked. When I go to the airport to pick up a refugee family and need a gate pass, I get one, no questions asked. When my black and brown coworkers go, they get the runaround. White privilege is having things work the way they’re supposed to work. It’s feeling safe when the police are in your neighborhood or pull you over. It’s going to a doctor’s office in a nice part of town and having no wait, no stares, no questions asked. It’s having doctors believe me if I’m telling them something hurts.[12]

My brother was killed suddenly and unexpectedly almost three years ago; losing him was the most painful thing I’ve ever experienced. He was riding his bike and was hit by a car. The agony of loss and the heartbreak my family endured is something that a lot of black families have experienced. A black mom held my brother’s hand as he died; her own son had been killed in a motorcycle accident the prior year. She prayed over John as he took his last breath and to this day, continues to comfort my mom, knowing the agony of loss herself.

Moms shouldn’t have to bury their sons, and when they do, something is deeply wrong. Let us mourn the lives that have been lost and beg for forgiveness for our national pride and sin. We have oppressed the poor and the foreigners and have upheld injustice, blind and deaf to the sobs of the hurting. Instead of staunchly defending our individualistic understanding of the gospel and the world around us, could the white Evangelical church choose to listen, learn, and repent? Could we embrace the gospel of scripture that is robust enough to be good news for everyone?

As I contemplate raising mixed kids (no Mom, I’m not pregnant yet). I want them to love God and their neighbors. I want them to grow up and pursue their dreams and have black and brown role models in leadership in the church and the community around us. If this is going to happen, and we’re going to see more people of color in positions of power and leadership, it will start with white people and churches taking a hard look at ourselves and our positions and asking, “Are my beliefs consistent with the gospel narrative?”

[1] I’m including these additional behavioral emphases to indicate the fundamentalist take on the gospel I learned. See Galatians to see how Paul responds to folks who try to add additional requirements onto following Jesus.

[2] The Navigators popularized the Bridge illustration in evangelical Christianity https://www.navigators.org/resource/the-bridge-to-life/.

[3] For a more in-depth explanation of white cultural values, see Dr. Robin DiAngelo’s book White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard to Talk to White People About Racism.

[4] Could the lack of explanation be one reason that Millenials are leaving the church in droves? https://www.pewforum.org/2019/10/17/in-u-s-decline-of-christianity-continues-at-rapid-pace/ Religious “nones” numbers are swelling. Perhaps many are disillusioned with the watered-down version of the gospel that Evangelicalism teaches.

[5] InterVarsity “The Big Story” https://2100.intervarsity.org/overview/big-story

[6] See this article for a brief explanation of the Christus Victor understanding of atonement. https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/essay/christus-victor/

[7] Ephesians 6:12

[8] Jim Wallis’ America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America is my current read on this subject.

[9] Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness documents the disturbing numbers of incarcerated Black people; disproportionately incarcerated for crimes committed in equal numbers by whites. Ava Duvernay and Jason Moran’s 2016 film 13th is another resource to look at this disparity.

[10] In Divided by Fath, Michael Emerson & Christian Smith give examples of parable of a weightloss camp (110-113) and reference John Perkins analogy of a rigged baseball game (127), to illustrate the historic and ongoing systemic influences of racism leading to unequal outcomes. Divided by Faith helped me think through this and is the basis for the puzzle analogy.

[11] I learned about the disproportionate effects of the GI bill not in my college’s American Heritage class, but when I read Debby Irving’s book Waking Up White: And Finding Myself in the Story of Race.

[12] This is not how many people of color are treated. See https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/racial-disparities-seen-in-how-doctors-treat-pain-even-among-children/2020/07/10/265e77d6-b626-11ea-aca5-ebb63d27e1ff_story.html. Also, in 2018 “the maternal death rate for black women was more than double that of white women: 37.1 deaths per 100,000 live births compared to 14.7.” https://www.vox.com/2020/1/30/21113782/pregnancy-deaths-us-maternal-mortality-rate